|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Is it worth training rolling skills in Volleyball’s defence? A study on women’s Olympic Games’ 2012 Vale a pena o treinamento de

rolamentos para as habilidades em defesa ¿Vale la pena entrenar los

rolidos como habilidad de la defensa |

|

|

|

*University of Porto – Faculty of Sports **Centre of Research, Education, Innovation and Intervention in Sport (Portugal) |

José Afonso* ** João David* | Inês Marinho* |

|

|

|

Abstract In high-level women’s volleyball, backcourt defence emerges as a key action for achieving elite performance. A wide range of defensive techniques has been developed to face more powerful, quicker, and varied attacks. Within this context, the rolling techniques have emerged to afford the players a quick reposition of their standing position, therefore getting back in the game without delay. After falling, the player rolls over her shoulders and gets back on her feet. However, we contend that techniques requiring rolling over the shoulders to recover positioning are expected to be rare. Therefore, it was our purpose to analyse the exact role of falls and falls with rolling in high-level women’s volleyball, and to provide guidance for coaches based on our data. Seven women volleyball matches from the Olympic Games’ 2012 were analysed. Results showed that falls correspond to just 9.1% of actions with the ball, while falls followed by rolling represent just 0.6% of the occurrences, thus confirming that rolling is not a relevant technique within the context of high-level women’s volleyball. Hence, although coaches should still teach the rolling over the shoulders, they should not devote much time in practice specifically for developing this technique. We contend that more than 5 minutes of specific rolling practice per training session is unreasonable, and it is actually likely to reduce performance, as time devoted to other, more relevant skills will have to be condensed. Keywords: Volleyball. Defense. Training rolling skills.

Resumo No voleibol feminino de alto nível, a defesa baixa emerge como uma ação-chave para alcançar performances de elite. Uma vasta gama de técnicas defensivas foi desenvolvida para fazer face a ataques mais potentes, rápidos e variados. Dentro deste contexto, as técnicas com rolamentos emergiram para proporcionar às jogadoras uma rápido recuperação da posição de pé, desse modo regressando ao jogo sem demora. Após cair, a jogadora rola sobre os seus ombros e regressa à posição vertical. Assim, foi nosso objetivo analisar o papel exato das quedas e, mais especificamente, das quedas com rolamentos sobre os ombros no voleibol feminino de alto nível, bem como providenciar aos treinadores sugestões de trabalho com base nos nossos dados. Foram observados sete jogos de voleibol feminino da fase final dos Jogos Olímpicos 2012. Os resultados mostraram que as quedas para contactar a bola correspondem a somente 9.1% das ações de intercepção da bola, enquanto as quedas seguidas de rolamentos representam apenas 0.6% das ocorrências, denotando que as técnicas de rolamentos não são relevantes no contexto do voleibol feminino de alto nível. Desta forma, embora os treinadores devam continuar a ensinar os rolamentos sobre os ombros como técnica de recurso, não deverão devotar muito tempo de prática especificamente para o desenvolvimento desta técnica. Defendemos, face aos dados, que mais de 5 minutos de prática específica de rolamentos por sessão de treino não é razoável, e pode mesmo prejudicar a performance, uma vez que o tempo dedicado a esta exercitação irá retirar tempo de prática a habilidades de jogo bem mais relevantes. Unitermos: Voleibol. Defensa. Treinamento rolamento.

|

|||

|

|

EFDeportes.com, Revista Digital. Buenos Aires, Año 18, Nº 184, Septiembre de 2013. http://www.efdeportes.com/ |

|

|

1 / 1

Introduction

High-level women’s volleyball is characterized by a strong component of playing in counter-attack or transition, also called complex II (Palao, Manzanares & Ortega, 2009). This is due to a greater equilibrium between attack and defence than what occurs in men’s volleyball (Selinger & Ackermann-Blount, 1986). As such, backcourt defence emerges as a key action in women’s volleyball (Afonso et al., 2012). A wide range of defensive techniques has been developed to face more powerful attacks, and also to counter quicker and more complex attack plays. Such techniques vary considerably; some are for regular application (e.g.: forearm passing), while others are designed for extreme situations (e.g.: the dive).

Within this context, the rolling techniques have emerged to afford the players a quick reposition of their standing position, therefore getting back in the game without delay (Bizzocchi, 2000; Ribeiro, 2004; Selinger & Ackermann-Blount, 1986). After falling, the player rolls over her shoulders and gets back on her feet. However, we contend that many times the players fall in positions that do not allow performing a roll (e.g.: after long slides the body is too stretched and lost momentum, hence the roll cannot apply) and/or ‘invite’ players to get up using other techniques, such as simply pushing-up against the floor or side rolling.

Thus, we state that techniques involving falling into the ground are already to be used only in special occasions; within the falls, those requiring rolling over the shoulders to recover positioning are expected to be rare. If true, this will present direct impact for volleyball training, as devoting much time for practicing such actions will not translate into better performance in the match. Therefore, it was our purpose to analyse the exact role of falls and falls with rolling in high-level women’s volleyball, and to provide guidance for coaches based on our data.

Methods

We analysed seven women volleyball matches from the Olympic Games’2012, namely the quarterfinals, semi-finals, and final. Overall, 27 sets were analysed, comprising 1199 plays that included 8549 actions with the ball. Plays with serve ace or error were also considered. Besides all proper interceptions of the ball, defensive actions including a fall when trying to reach the ball were also considered. The purpose was to register all actions directly related to contacting the ball.

Match analysis was conducted using high-definition 1080p videos including the entire matches. Every play was observed at least once. When necessary, the play was observed twice in order to enhance the quality of the observation.

Reliability calculation considered one of the analysed matches, consisting of five sets and 228 plays, corresponding to 19.0% of the sample. For intra- and inter-observer reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha ranged from 0.83 to 0.86, which is considered reliable (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

Results

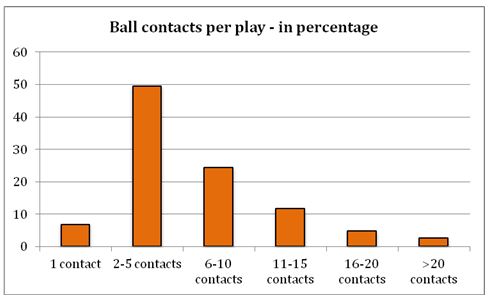

We start our analysis by providing an overview of the number of ball contacts per play, as shown in table 1.

Table 1. Frequency table according to number of ball contacts with the ball per play

Around 6.9% of plays are comprised by just one ball contact, i.e., a serve error or an ace. Almost 50% of the plays consist of 2 to 5 ball contacts. Usually, these refer to a play in which there is a serve, followed by a regular three-contact play by the receiving team, plus a touch by the block or the backcourt defence. There is also a considerable amount of plays consisting of 6 to 10 ball contacts (24.4%), and a reasonable amount of plays of 11 to 15 ball contacts (11.7%). Plays surpassing 15 contacts with the ball are less common, totalizing less than 8% of all the plays.

Figure 1. Number of ball contacts per play (in percentage)

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics concerning the plays. As is apparent, there is a wide variation in the number of ball contacts per play (minimum of 1 and maximum of 38), but both median and mode agree in a central value: 5 ball contacts per play is the most common occurrence.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics concerning the plays

The actions involving falling into the floor were of the following types: a) dive followed by frontal slide; b) lateral lunge followed by lateral slide; c) falling over the buttocks after defending the ball; and d) type b or c falls, but followed by a rolling over the shoulders in order to get back on standing position. Analysis of this competition reveals there is less than 1 fall per play. The median and mode demonstrate that the most common occurrence is 0 falls per play, meaning that usually there is no need of the players to fall when trying to intercept the ball. Type d falls, i.e., those involving rolling over the shoulders to get back to standing position, are nearly insignificant, as shown by all central values data.

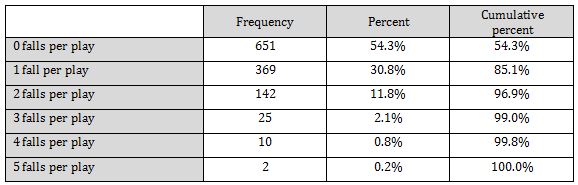

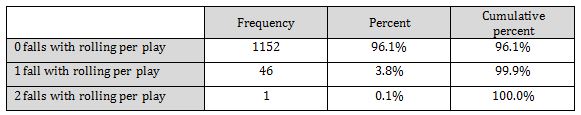

Analysing the number of falls per play in greater detail (see Table 3), it is evident that almost 55% of the plays do not involve players having to fall into the court. A little above 30.8% of plays involve 1 fall to intercept the ball, and around 12% of plays imply 2 falls. More than two falls per play constitute rare occurrences.

Table 3. Frequency table according to number of falls per play

The same logic of analysis was further applied to falls with rolling over the shoulders (see Table 4). It emerges clearly that these types of falls are rare within the high-level women’s volleyball game. Indeed, 96.1% of the plays do not involve any such action. Only circa 4% of plays actually require a roll to be performed.

Table 4 . Frequency table according to number of falls with rolling over the shoulders per play

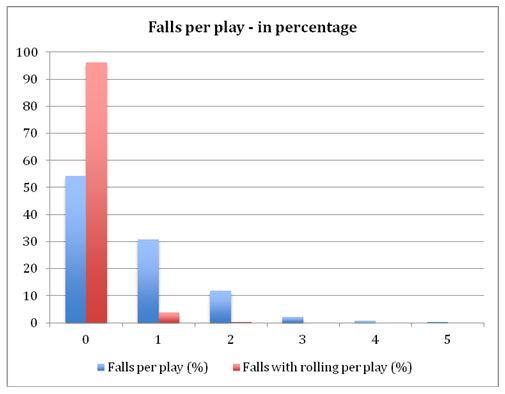

Figure 2 provides a good picture of the general role played by falls within the game.

Figure 2. Number of falls per play (in percentage)

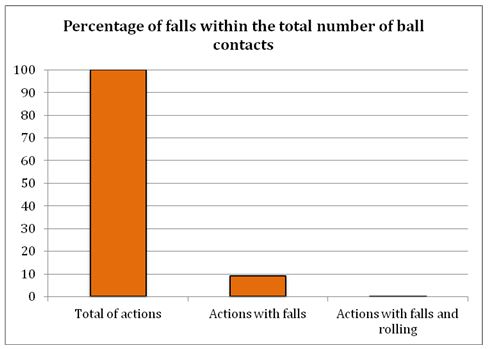

As observed, falls represent a reduced percentage of occurrence, especially falls with rolling, falling almost entirely into the 0 category. However, lets remember that the 1199 plays translated into 8549 actions with the ball or attempts to intercept the ball. Overall, just 9.1% of actions with the ball involved falling into the floor (n=778). Moreover, only 0.6% implied rolling over the shoulders (n=48). Figure 3 provides a visual of these values.

Figure 3. Percentage of falls within total number of ball contacts

Discussion

Our purpose was to analyse the role of falls and falls with rolling in high-level women’s volleyball. We first observed that, in the Olympic Games’ 2012, most plays extend from 1 to 10 ball contacts (80.9%), denoting exchanges with a serve, a side-out or complex I, and one or two counter-attacks. These points towards a type of plays based on intensity and not on endurance. Indeed, both the median and the mode of ball contacts per play is five, meaning the team playing in counter-attack will lose the point at the first contact (either blocking or defending).

More directly related to our intentions, it was highlighted that the number of falls per play was below the unit, while the number of falls with rolling per play was close to zero. Of the total number of plays (1199), 30.8% required one fall to be used, and only 12% required more than one fall. As for falls implying rolling over the shoulders to recover standing position, they emerged in only a mere 3.9% of plays. Therefore, in a very straightforward manner, the rolling techniques seem to be nearly irrelevant for the overall performance in the match. If instead of the total number of plays we now consider the total number of ball contacts (8549), we understand that falls correspond to just 9.1% of actions, while falls followed by rolling represent just 0.6% of the occurrences, thus confirming that rolling is not a relevant technique within the context of high-level women’s volleyball. Furthermore, it is a technique in which the players will momentarily lose sight of the ball, unlike other more traditional forms of recovering the standing position.

This simple fact has direct implications for managing the training process. Although coaches should still teach the rolling over the shoulders, they should not devote much time in practice specifically for developing this technique. Its natural emergence in contexts such as reception, defensive or setting drills will suffice. As rolling embody a mere 0.6% of ball contacts within a game, time devoted to specifically practice it should be extremely reduced. Moreover, we don’t have to practice ball contacts only, but additionally we have to perform actions without the ball, such as positioning, adjusting, simulating, among others. For example, over the course of a season, and considering 2-hour training sessions, practicing the rolling for 1.2 minutes per session would already mean 1% of training time, above what’s required in the match. Practicing 5 minutes of rolling per training session (again, in a typical 2-hour session) would already allocate above 4% of training time for this action. With the exception of certain introductory drills, at the very beginning of familiarizing with this skill, we contend that more than 5 minutes is an unreasonable practice, with no translation into better performance in the game. Actually, it is likely to reduce performance, as time devoted to other, more relevant skills will have to be condensed.

References

-

Afonso, J.; Garganta, J.; McRobert, A.; Williams, A.M.; Mesquita, I. (2012). The perceptual cognitive processes underpinning skilled performance in volleyball: Evidence from eye-movements and verbal reports of thinking involving an in situ representative task. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 11(2), 339-345.

-

Bizzocchi, C. (2000). O voleibol de alto nível – da iniciação à competição. São Paulo: Fazendo Arte Editorial.

-

Palao, J.M.; Manzanares, P.; Ortega, E. (2009). Techniques used and efficacy of volleyball skills in relation to gender. International Journal of Performance Analysis of Sport, 9(2), 281-293.

-

Ribeiro, J. (2004). Conhecendo o voleibol. Rio de Janeiro: Sprint.

-

Selinger, A.; Ackermann-Blount, J. (1986). Arie Selinger’s Power Volleyball. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

-

Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53-55.

Another articles in English

|

Búsqueda personalizada

|

|---|---|

|

EFDeportes.com, Revista

Digital · Año 18 · N° 184 | Buenos Aires,

Septiembre de 2013 |

|