|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

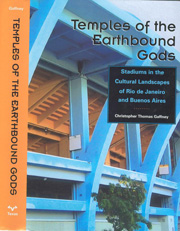

Acknowledgements and forewords in 'Temples of the Earthbound Gods. Stadiums in the Cultural Landscapes of Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires' |

|

|

|

*Keele University (Great Britain) **Durham University (EE.UU.) |

John Bale* Chistopher Gaffney** geostadia@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

http://www.efdeportes.com/ Revista Digital - Buenos Aires - Año 13 - Nº 128 - enero de 2009 |

|

|

1 / 1

Acknowledgements

This book would have been impossible without the help, guidance and assistance of my friends and colleagues in Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Durham, North Carolina and Austin, Texas, among other places. In Buenos Aires I am particularly indebted to Tulio Guterman whose insight, friendship and connections opened many doors that I never knew existed. Tulio introduced me to a slew of academics, journalists and fútbol cognoscenti among whom Julio Frydenberg, Roberto Di Giano, and Hugo Comesaña stand out. I am also grateful to the Gil and Tomasetti families for opening homes in some very difficult times. Early versions of the Buenos Aires chapters were read by Elizabeth Jelin and Ines Valdez, and their comments were immensely valuable in shaping the final version. Manuel Balan provided the muscle necessary to push into the popular section of at least one stadium. The rest I managed with the help and acerbic humor of thousands of unknown porteños. Es para vos, para vos.

In Rio de Janeiro I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Gilmar Mascarenhas de Jesus whose hospitality and geographic vision helped to shape my perceptions of a cidade marahvilhosa. Fernando Ferreira also extended untold kindnesses and his profound knowledge of and passion for Vasco da Gama were inspirational. Thanks are also due to Mauricio, Davidson, Jair, Renato Trindade, the geography students and faculty at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) and at the Federal University of Minas Gerais - Carangola. Abbie Bennett earns full marks for sharing the costs of a one room hovel in Copacabana during the fieldwork. Rodigo Nunes helped me pick out my first sunga and instructed me in some of the finer details of carioca culture. Gonzalo Varela and Sofia Alencastro provided critical logistical and moral support in São Paulo and I am grateful for their friendship and la Nina preciosa.

In the USA I am indebted to the guidance and support of Paul Adams, who edited and pushed me through the dissertation so this book could be written. Thanks also to those who have participated in conference sessions and contributed to the larger theoretical discussion, particularly Hunter Shobe and George Roberson. Casey and Kristine Kittrell deserve more than I can give in return for their epicurean friendship. Brian Godfrey and Bert Bjarkman all read early versions of chapters and I am grateful for their feedback. Paul McGinlay and the Trinity University Men's Soccer team deserve some kind of trophy for allowing me to wax philosophic about kicking a ball around a field. I imagine it would look like Rodin's Thinker dressed in a Paris St. Germain shirt with a soccer ball underfoot. Thanks also to Jason Reyes and David Salisbury for their design and cartographic aid.

Of course, none of this would have been remotely possible without the faith, confidence, infusions, airline passes and support of my parents and brothers. And finally, mil beixos to Brenda Baletti whose love and life bring joy to my heart.

Chris Gaffney (North Carolina, USA)

Foreword

The stadium is a significant feature of places ranging from metropolitan centers to small towns and villages. The stadium, like the church, is a place of congregation - and some would say worship. It is a much-loved place that folks often want to retain as a community focus and a sense of pride. But the stadium, like many other things, can be seen in a different light. It is arguably the most secure building in the city: Hence, it has been used as a site of incarceration for criminals, immigrants and 'others'. In addition to the church, several other metaphors seek to essentialize the stadium - a garden, a theatre and a prison. Stadiums vary in size, function and design. It is often felt that stadium architecture is becoming more standardised - the concrete bowl or (after Le Corbusier) a machine for making sport. What is standardized are the rules and regulations, manifested in the layout of the 'playing' area with its predictable lines, zones and limits. In the stadium are found predictable geometries. The 'sameness' that characterizes the sports site makes it a global phenomenon. A soccer pitch has to have the same dimensions in London, England as in London, Ontario. Geography has to give way to geometry.

Difference can be found in the architecture that is required to contain the sporting action and to provide for spectators. Compare, for example, the postmodern exterior of the Beijing Olympic stadium with the gothic, granite facade of the 1912 Olympic stadium at Stockholm. The stadium is a melding of horticulture and architecture. I find it interesting that while rules and regulations govern the traditional layout of the horticulture (i.e. the playing 'field'), the surrounding architecture is given free reign in terms of design. And while there are written rules for the players there are none for the spectators. Over time it has become meaningless to call a stadium after its sport. A baseball 'field' or a 'football ground' can be turned into a convention center, almost at the switch of a button. Instead of being a much-loved site it has become a multi-purpose facility, typified by domed arenas with their artificial lighting and plastic greensward.

Written works on the stadium cover a vast spectrum. Many of them relate to the summer sports of baseball and cricket. Others allude to football stadiums, hockey arenas and swimming pools. There are few sports whose immediate milieu has not been written about in some form. A book can take up a single stadium. The famous rugby ground in my home city of Cardiff has been eulogised in Taff's Acre: A History and Celebration of Cardiff Arms Park. Also on my bookshelf I have William Jasperson's The Ballpark, a paean to Fenway Park, Boston. From France Les Yeux du Stade is an insightful text on Colombes, the stadium in Paris that is dubbed 'Temple du Sport Français'. Other books take a broader picture. For example, Philip J. Lowry's Green Cathedrals celebrates the 271 Major and Negro League ballparks past and present. Similarly, Simon Inglis has surveyed The Football Grounds of Europe. Each of these are valuable and informative works but they are not the writings of the trained scholar and there is a tendency for them to be snobbishly labelled 'coffee table' books. At the other end of the spectrum a substantial amount of writing is the result of heavier 'academic' work, scripted by those among us who are paid to study sport. Stadion: Geschichte, Architektur, Politik, Ökonomie is a stunning 450 page tome published in Austria and essayed by an interdisciplinary group of scholars from several nations. In The Stadium and the City I co-edited a similar kind of multi-authored publication. Other 'heavyweight' texts are scattered among journal articles and monographs. They deal with such subjects such as the costs and benefits of stadium relocation and the economic impact of a stadium on its surrounding community. They command a relatively small audience despite the burgeoning field of sports studies.

In the representation of the homes of sport the 'popular' and the 'academic' sometimes come together. Novelists allude to the stadium in ways that inform our senses as well as supply the 'facts'. Philip Roth is a case in point. In two of his early works he reveals the place and 'meaning' of the baseball stadium in the life of the troubled Alex Portnoy while in 'Goodbye Columbus' he deconstructs the sport-spaces (swimming pools, basketball courts, high school running tracks) of suburban New Jersey. But also take, for example, the delightful little book by A. Bartlett Giamatti (a renaissance scholar and former President of Yale University and Commissioner of Major League Baseball) titled Take Time for Paradise. In this context the baseball stadium is more than a 'temple': It is paradise itself. Also in a more humanistic vein, Christian Bromberger, in Le Match de Football, has analysed the ritual dimensions found in stadiums in Marseille, Naples and Turin through the eyes of an anthropologist and ethnologist.

To these highly selective studies must now be added the work of Chris Gaffney. In the pages that follow he supplies a novel and wide-ranging view of the world game of soccer - or football as Europeans insist on calling it. His work is wide-ranging but also narrowly focussed on two major soccer cities in South America - Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro. He is not the first to study soccer in these cities. Eduardo Archetti has researched the former while the latter was the focus of the pioneering study by Janet Lever. Each of these eminent scholars was an anthropologist. Gaffney was trained as a geographer and has applied the geographer's broad gaze to a wide field. He works through a variety of scales - from murals and monuments to rituals and records.. He paints views of what it is like to be in the stadiums of these two giant cities, teasing out examples of 'sense of place' and genius loci. At a different scale he explores the global football scene, including of soccer's history and its diffusion to, and adoption in, Latin America.

My view is that this book, with its lavish collection of photographs, maps and diagrams and its clear and lively writing, deserves to be read and digested by readers spanning a variety of disciplines. Unquestionably, it makes a major contribution to geographical studies of sport but it has much to tell students and teachers in cognate fields. It will also satisfy the Latin Americanist and the informed sports fan.

John Bale (Crewe, England)

|

|

|---|---|

|

revista

digital · Año 13 · N° 128 | Buenos Aires,

enero de 2009 |

|